Healthspan vs. lifespan: two ways to measure longevity

Lifespan describes how many years a person lives. Healthspan measures the quality of those years. Learn about the difference between the two.

What to know

Lifespan is how many years a person lives. Healthspan measures how many years they live in good health

For scientists, “good health” includes years lived without being diagnosed with a chronic disease associated with death

The measures of certain biomarkers, including HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, HbA1C, and C-reactive protein, are associated with longer healthspans

Eating a healthy diet, exercising, and sleep are associated with longer healthspans, as are behaviors which help clear out old, malfunctioning cells

We’re living longer than ever, and the increases in our longevity are happening fast.

Since the mid-twentieth century, global life expectancy has risen from 47 to 73 years. [1]But now, scientists are focused on adding life to those extra decades—increasing not just lifespan, but “healthspan,” a term for the number of years we’re living healthy.

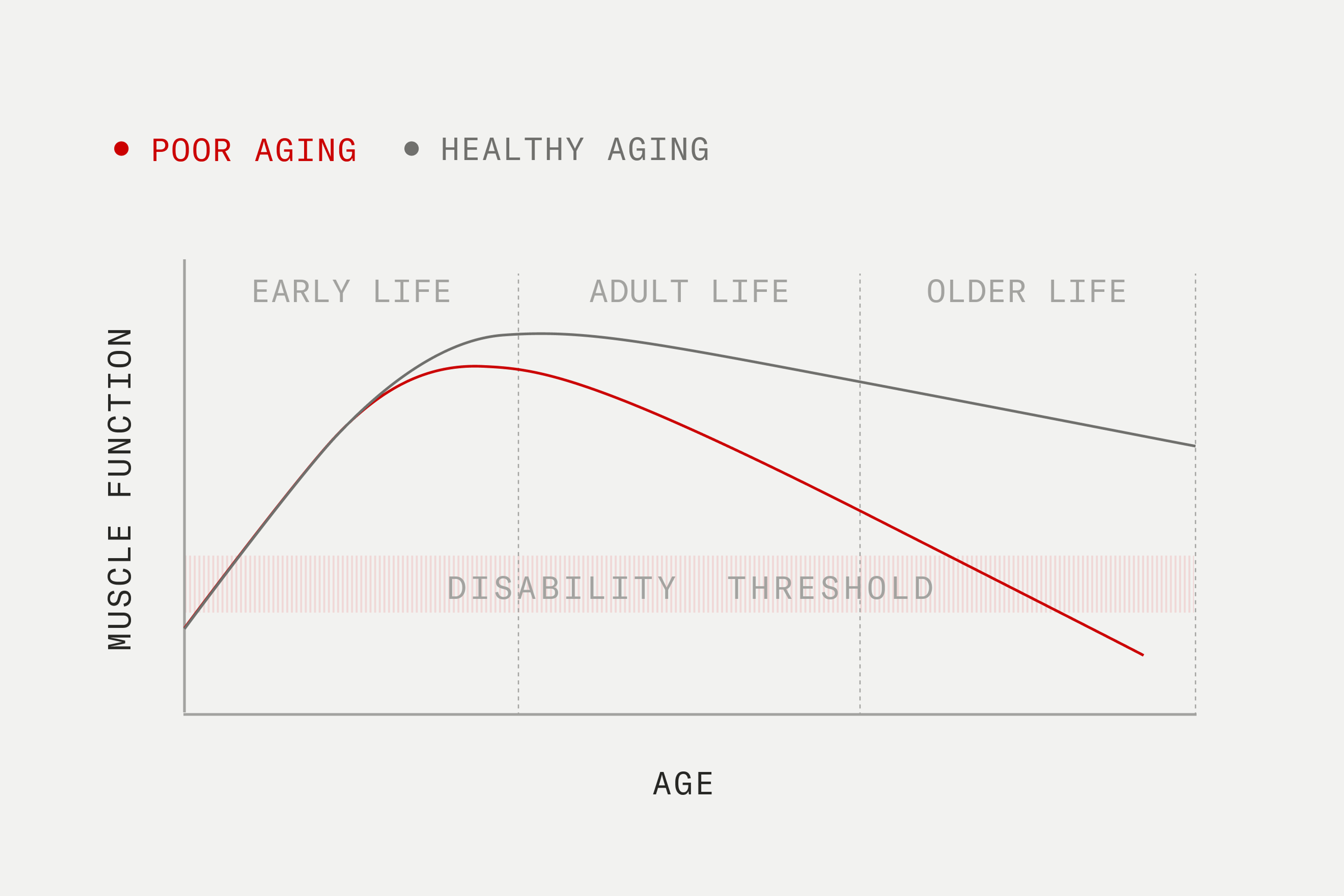

Muscle function in Healthy aging VS Poor aging

The difference between lifespan and healthspan

“Lifespan” refers to the number of years you live: A person who lived to be 95 had a lifespan of 95 years. But “healthspan” refers to the number of years someone lives in good health. Scientists refer to those years of “good health” ending when someone contracts a chronic condition or disease associated with mortality: Cancer, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, cardiovascular disease.[2]

It’s estimated that people live an average of about nine years longer than their healthspan, surviving—but not really thriving—for almost a decade.

Biomarkers that predict healthspan

One way scientists are hoping to help extend healthspan is by measuring biomarkers: These substances accumulate in our blood, spinal fluid, or elsewhere in the body and are associated with disease risk. When your doctor measures the cholesterol levels in your blood, for example, that’s a biomarker. A few biomarkers have been shown to have a strong correlation to longer healthspans.

Fasting blood glucose:

Also called your fasting blood sugar, this is a measure of the amount of glucose that’s circulating in your blood when you’re at rest. Studies have found a link between elevated fasting blood sugar and the development of diseases like diabetes and heart disease.[3]

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C)

This is a measure of how much glucose is in your blood, measured over three months, expressed as a percentage. In a study, for every 0.4 percent increase in HbA1C, the risk of contracting a chronic disease—ending healthspan—increased by 29 percent over a 16-year period for those studied.[4]

Triglycerides

When you eat excess calories, your body stores them as triglycerides—the most common type of fat in your body. When triglyceride levels are higher than 150 mg/dL in your blood, your risk of cardiovascular disease is increased.[5]

C-reactive protein (CRP)

Elevated levels of this protein are associated with chronic inflammation. When CRP levels are chronically high, risks of cardiovascular disease, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s all increase.[6]

High-density lipoprotein (HDL):

HDL is the “good cholesterol,” carrying away “bad” LDL cholesterol in your blood. Studies have found a strong inverse relationship between high HDL levels and developing chronic disease.[7]

5 ways to extend your healthspan

About 20-25 percent of our lifespan is based on our genetics, with the rest dependent on our environment and lifestyle.[8] While we can’t control all those factors, some simple strategies have been shown to improve both healthspan and lifespan:

Exercise

Moving your body is associated with reductions in chronic inflammation, as well as lowered risk for diseases of aging.[9] And it doesn’t need to be hours of high-intensity work, either: Performing low- to moderate-intensity cardio for 30 minutes, three to five times per week, has been associated with improving cardiovascular disease outcomes[10].

Eat a Mediterranean diet

A recent study showed that eating a Mediterranean diet—rich in polyunsaturated fats and leafy greens— could lower “biological age.” [11]Like healthspan, biological age is a different way of measuring age: When your biological age is lower, you’re “younger,” health-wise, compared to others born the same year.

Practice intermittent fasting

Calorie restriction has been found to improve healthspan, but not getting enough nutrients in the long term can have a detrimental impact on health. Intermittent fasting is a safe alternative that helps the body reshape itself in a way that can extend a healthy life. While fasting, your body undergoes a process called autophagy, cleaning out malfunctioning cells in favor of new, healthier ones. See this guide for more on how—and why—a fasting regimen can help with healthy aging.

Take supplements that target the aging process

As we age, our mitochondrial function declines, resulting in an increased disease risk[12]. Along with exercise, fasting, and a healthy diet, certain supplements, like Urolithin A, can help clear out these damaged mitochondria in favor of new ones that function properly. [13]

Mitopure Softgels

Bestseller4.4 · 3124 reviews

The simplest form of Mitopure

Get regular sleep:

Lost sleep won’t just make you groggy. Sleeping less than seven hours per night has been associated with increased risks of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and depression.[14]

Final words

The old adage about “adding life to your years” has never been more true: Scientists are devoting research and time into extending not just how many years we live, but the quality of that extra time. While evidence for what optimizes healthspan continues to evolve, a few simple changes can increase your healthy longevity ... starting now!

Authors

Written by

Editorial Staff

Reviewed by

Senior Manager of Nutrition Affairs

References

- ↑

Garmany, A., Yamada, S. & Terzic, A. Longevity leap: mind the healthspan gap. npj Regen Med 6, 57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-021-00169-5

(https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-021-00169-5) - ↑

Li X, Ploner A, Wang Y, et al. Clinical biomarkers and associations with healthspan and lifespan: Evidence from observational and genetic data. EBioMedicine. 2021;66:103318. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103318

- ↑

Park C, Guallar E, Linton JA, Lee DC, Jang Y, Son DK, Han EJ, Baek SJ, Yun YD, Jee SH, Samet JM. Fasting glucose level and the risk of incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Diabetes Care. 2013 Jul;36(7):1988-93. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1577. Epub 2013 Feb 12. PMID: 23404299; PMCID: PMC3687304.

- ↑

Li X, Ploner A, Wang Y, et al. Clinical biomarkers and associations with healthspan and lifespan: Evidence from observational and genetic data. EBioMedicine. 2021;66:103318. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103318

- ↑

Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, Bittner V, Criqui MH, Ginsberg HN, Goldberg AC, Howard WJ, Jacobson MS, Kris-Etherton PM, Lennie TA, Levi M, Mazzone T, Pennathur S. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2292–2333. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726 (https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726)

- ↑

Luan YY, Yao YM. The Clinical Significance and Potential Role of C-Reactive Protein in Chronic Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1302. Published 2018 Jun 7. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01302

- ↑

Milman S, Atzmon G, Crandall J, Barzilai N. Phenotypes and genotypes of high density lipoprotein cholesterol in exceptional longevity. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2014;12(5):690-7. doi: 10.2174/1570161111666131219101551. PMID: 24350928; PMCID: PMC4087084.

- ↑

Ruby JG, Wright KM, Rand KA, Kermany A, Noto K, Curtis D, Varner N, Garrigan D, Slinkov D, Dorfman I, Granka JM, Byrnes J, Myres N, Ball C. Estimates of the Heritability of Human Longevity Are Substantially Inflated due to Assortative Mating. Genetics. 2018 Nov;210(3):1109-1124. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301613. PMID: 30401766; PMCID: PMC6218226.

- ↑

Huffman DM, Schafer MJ, LeBrasseur NK. Energetic interventions for healthspan and resiliency with aging. Exp Gerontol. 2016;86:73-83. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2016.05.012

- ↑

Hansen D, Niebauer J, Cornelissen V, et al. Exercise Prescription in Patients with Different Combinations of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Consensus Statement from the EXPERT Working Group. Sports Med. 2018;48(8):1781-1797. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0930-4

- ↑

Yaskolka Meir, A., Keller, M., Hoffmann, A. et al. The effect of polyphenols on DNA methylation-assessed biological age attenuation: the DIRECT PLUS randomized controlled trial. BMC Med 21, 364 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-03067-3 (https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-03067-3)

- ↑

Haas RH. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging and Diseases of Aging. Biology. 2019; 8(2):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology8020048 (https://doi.org/10.3390/biology8020048)

- ↑

Andreux PA, Blanco-Bose W, Ryu D, Burdet F, Ibberson M, Aebischer P, Auwerx J, Singh A, Rinsch C. The mitophagy activator urolithin A is safe and induces a molecular signature of improved mitochondrial and cellular health in humans. Nat Metab. 2019 Jun;1(6):595-603. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0073-4. Epub 2019 Jun 14. PMID: 32694802.

- ↑

Sleep and Chronic Diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/chronic_disease.htmll

Disclaimer

The information in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. Always consult with your medical doctor for personalized medical advice.

•

Nutrition•

First-of-Its-Kind Longevity Gummy Launched

•

Skincare•