What happens when skin ages?

The science of skin aging, how it happens, what to expect and steps you can take to slow down the effect of internal and external stressors

You don’t look your age!

It’s such a flattering thing to hear. If it happens to you, it may be because your biological age and chronological age don’t match up. [1]Lucky you! But what causes the skin to age, what can we expect as we get older, and is there anything we can do to slow down this process?

Highlights

- Skin aging is a natural consequence of the passage of time (chronological aging), but two people of the same age might not look the same age (biological aging)

- Skin changes like dryness, sagginess, wrinkles, and hyperpigmentation are a result of reduced elastin production, a decline in collagen deposition, and water loss – but can vary according to skin type and ethnicity

- The changes that happen to the skin cells are caused by intrinsic aging (happening on the inside of the body) and extrinsic aging (environmental or lifestyle factors), both affecting energy metabolism in skin cells

- Energy production in the cell is at the core of skin health because energy is needed to fuel the most basic functions of the skin.

- Mitochondria, the powerhouse inside the cell, play a vital role in skin health

- Dysfunctional mitochondria can lead to skin aging

- Eating a healthy diet, avoiding smoking, and reducing stress can help to rejuvenate your skin

- Scientists are working on new ways to improve mitochondrial health which may help to keep skin looking and feeling youthful

Why does skin age?

The factors contributing to skin aging originate inside the body (intrinsic) and also outside the body (extrinsic).[2]

Jeanne & Susan: Effect of smoking, sun & stress on the skin of twins. Aged 61, the twin on the right is a smoker and regular sunbather.

Extrinsic skin aging happens when skin is exposed to sunlight (photoaging), smoking, or pollution.[3] Exposure to these extrinsic stressors releases free radicals, which damage skin cells and lead to skin aging.

Darker skin is better protected from photoaging due to higher levels of melanin, which can lead to fewer wrinkles in people with melanin-rich skin.[4]

Intrinsic skin aging happens due to normal biological processes inside the body that release free radicals. For example, when we metabolize food into energy, free radicals are produced that can damage cells. When we’re young, our cells are very efficient at producing energy to fuel the different functions of our skin, while clearing excess free radical production. This keeps skin cellular damage at bay. However, as we get older, cellular processes become dysfunctional, leading to more production and less clearing of free radicals, and consequently more cell damage[5]. In turn, the skin becomes less resilient and less able to protect itself from external stressors.

What happens in the skin layers as we age?

The skin is the biggest organ in the body and has a big appetite for energy.[6] Energy production in skin cells can determine our skin’s health because energy is needed to support the skin’s very important roles beyond our physical appearance. Our skin is:

- A physical and chemical barrier to protect us

- An important part of our immune system

- Our moisture and temperature regulator

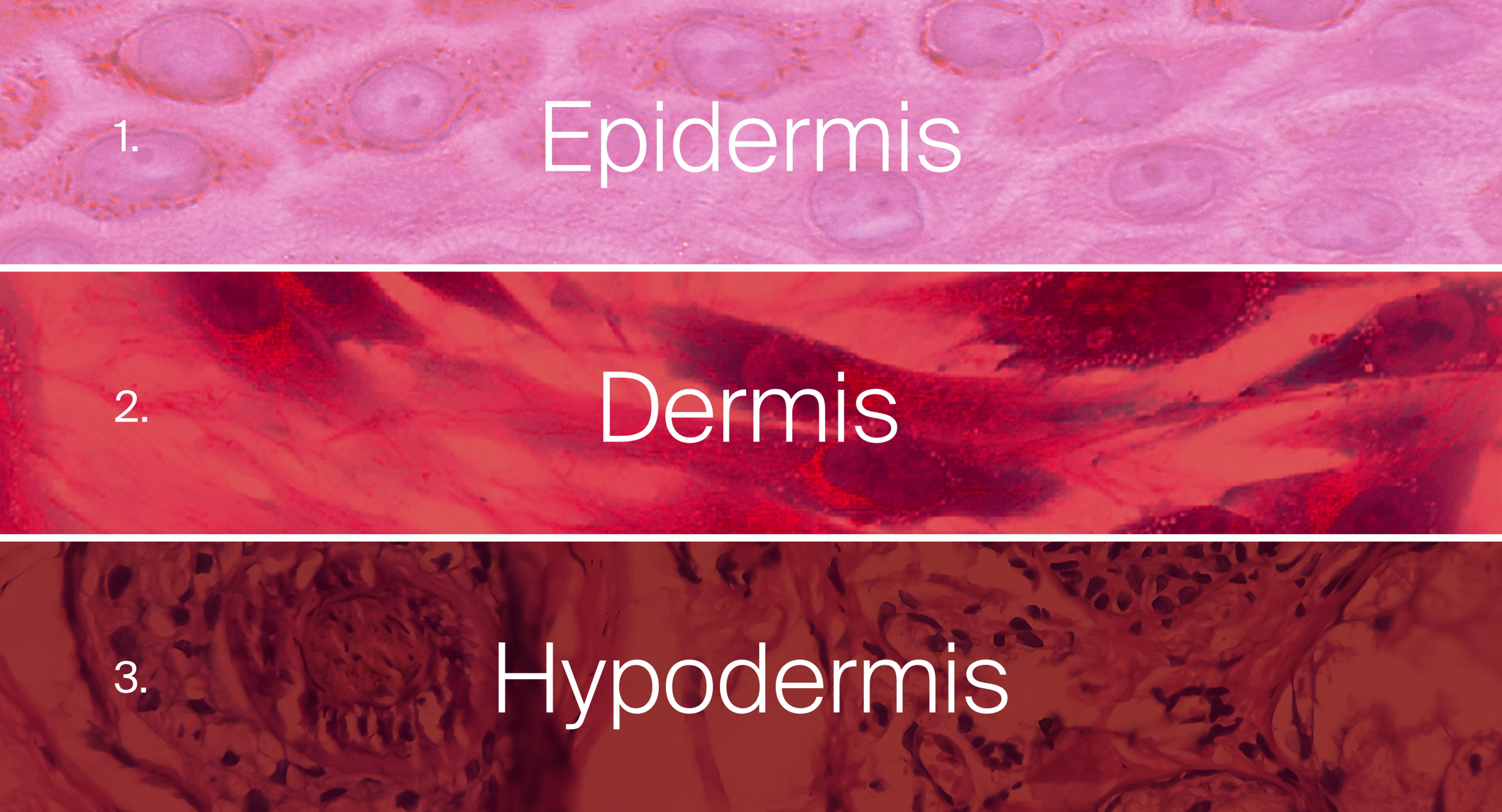

Our skin is composed of 3 layers of specialized cells. As we age, these cells become less efficient at producing energy to fuel their specific functions, eventually leading to signs of aging:[7]

1. The epidermis is mainly composed of keratinocytes that impart strength and drive skin cell renewal, and melanocytes which produce melanin. As we age, the aging keratinocytes are less able to maintain a strong skin barrier and the melanocytes’ melanin production becomes less even, leading to dark spots.

2. The dermis is made up of fibroblasts which produce collagen and elastin giving the skin its thickness and elasticity. As our cells age, fibroblasts produce less collagen and elastin leading to thinner more fragile skin.

3. The hypodermis is made up of adipocytes or fat cells and is the bottom layer of the skin. It protects the body from injury, is a very powerful insulator, and is rich in connective tissue, connecting the skin to the muscle. As we age, the hypodermis becomes thinner and less connective tissue is available to link the skin to the muscle, contributing to skin sagging.

Skin aging is a cellular affair

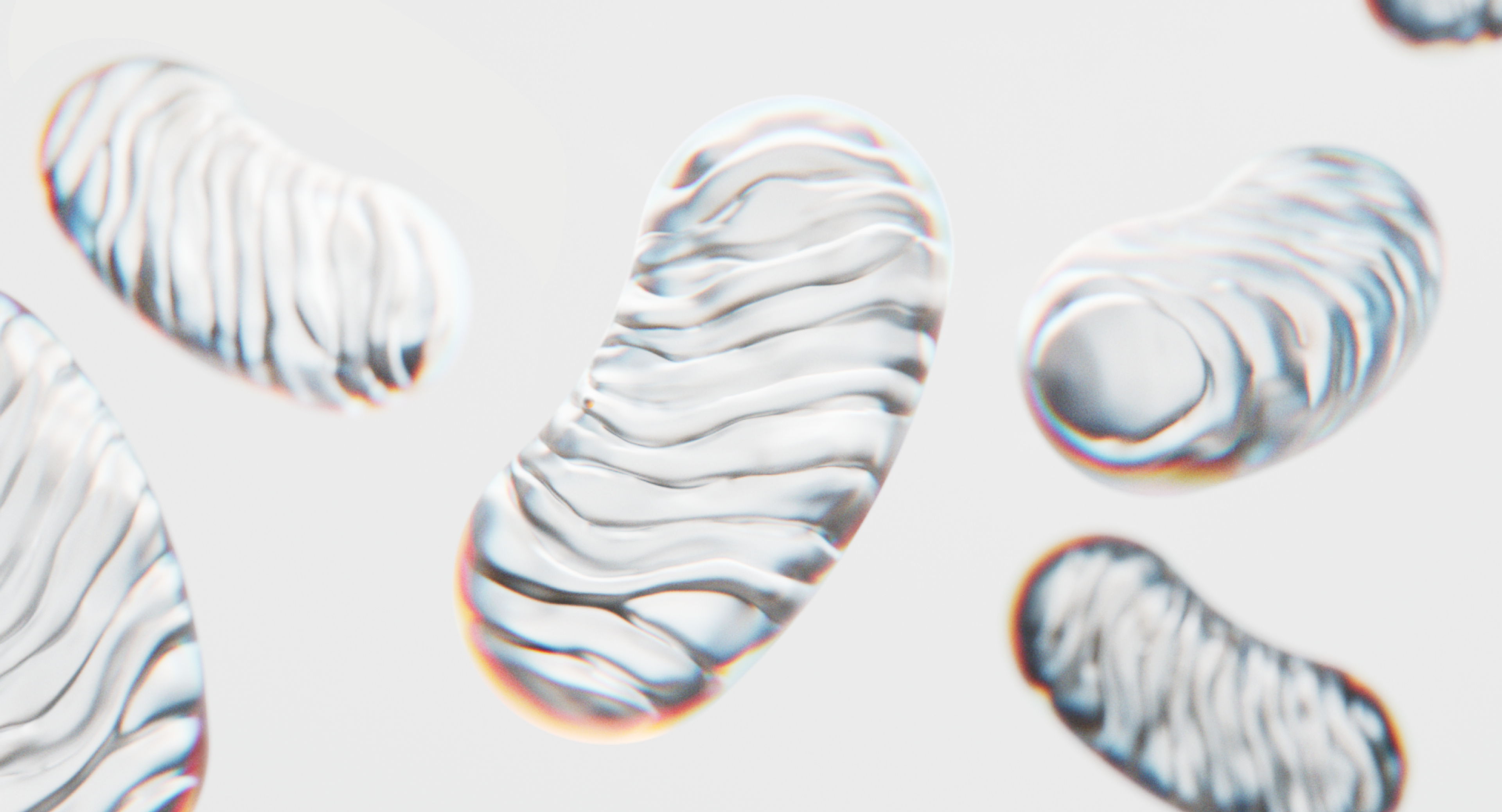

The mighty mitochondria: The mitochondria are the powerhouse inside our cell. Scientists believe they may hold the key to longevity. They control the life and death of the cell (cellular renewal). Mitochondria need renewal and replacement themselves over time. This process is called mitophagy. Mitophagy is very important for cellular renewal.

Cell renewal in the body, including skin cell renewal, is regulated by the mitochondria inside the cell.[8] As the mitochondria become “worn”, new ones are needed. If new mitochondria can be efficiently replaced, our cells will be renewed and remain healthy and resilient. However, as we age the cell renewal of our keratinocytes becomes less efficient. This reduces the capacity of our skin cells to maintain and repair the protective barrier and leads to skin thinning, water loss, and poor wound healing. We also have fewer melanocytes as we age, leading to uneven pigmentation and age spots. Finally, fibroblasts produce less collagen and elastin, causing the skin to lose its thickness and elasticity.

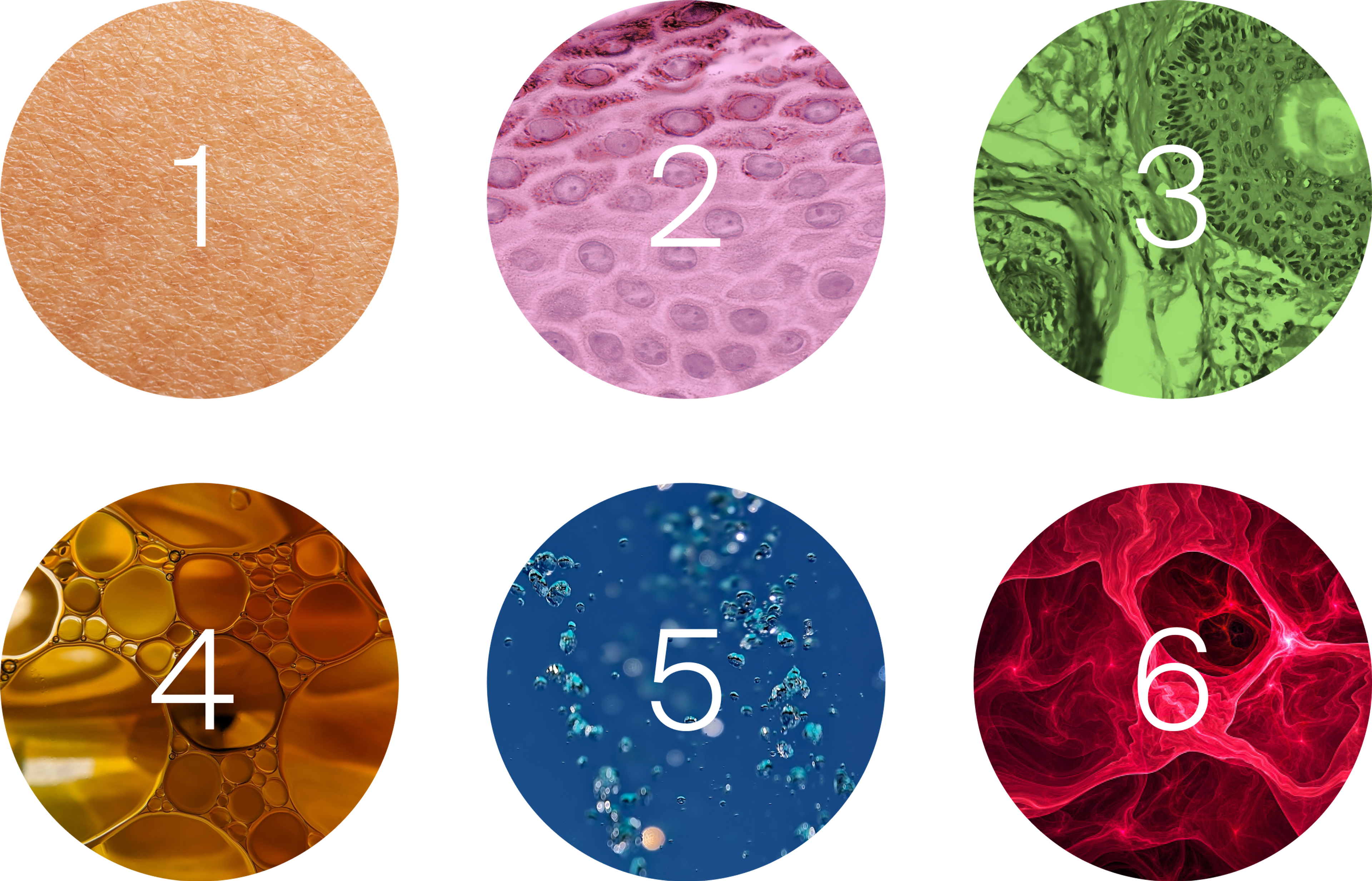

Stages of skin aging: What to expect?

Skin aging can vary depending on skin type and ethnicity, but in general you can expect the following:[9]

1. Skin thickness reduces every decade by about 6%

2. Keratinocytes change shape

3. Melanocytes decrease

4. Sebum production decreases by as much as 60%

5. Water and fat content of the skin declines

6. Collagen and elastin decrease

The evolution of skin through the years

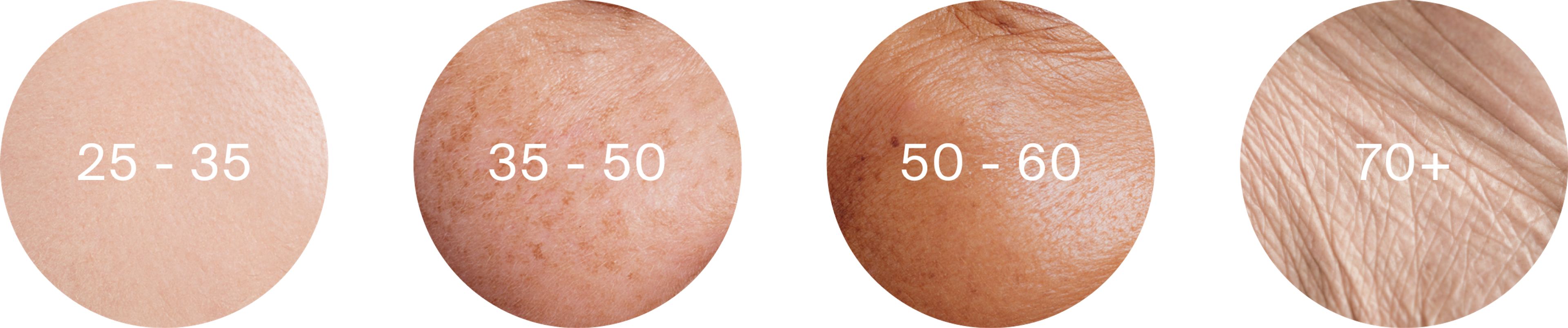

It is not easy to predict the “schedule” at which our skin will age, in part because this greatly depends on nutrition, lifestyle, and skin health-related habits. That said, dermatologists and cosmetic specialists do agree on a rough timetable for stages of skin aging:[10]

Skin evolution through the years

Age 25 - 35: The early signs of aging can start to appear, with fine lines linked to facial expression, and the early signs of crow’s feet. Collagen and elastin production can start to slow down, and the skin begins to lose the radiance it once had.

Age 35-50: Changes in skin thickness and elasticity become more noticeable. Fine lines and wrinkles appear at rest. Larger pores may appear, some may notice the development of bags underneath the eyes. The cheeks sag as they lose volume. Some may notice lines, wrinkles and sagging under the chin and in the neck area. The signs of earlier sun-damage may start to appear.

Age 50-60: More pronounced changes become visible due to further slow down in collagen and elastin production. Bone mass may also have started to reduce, which can change the contours of the face. Gravity is taking more of an effect, causing the skin to hang, and maybe even pulling the nose downwards. The skin starts to be thinner and more fragile. Wrinkles may be present on the entire face at rest. The next stage.

Age 70+: Wrinkles are marked and deep. The cheeks and skin on the edges of the chin, along with around the eyes and eyelids may sag. Age spots due to sun damage will be visible. Around the eyes, cheeks and foreheads the wrinkles may develop a “crisscross” pattern.

Can science help us to reverse the signs of aging?

Getting old is a fact of life, but science is teaching us more and more about how to delay skin aging. The answer may lie inside the cell, and more specifically, the mitochondria. The skin needs a lot of energy to renew itself, and dysfunctional mitochondria contribute to skin aging, so scientists are looking into bioactive ingredients that can boost the energy inside the cell by keeping the mitochondria healthy.

Want to know more? Look out for future posts where we’ll learn more about mitochondria and skin health

Authors

Written by

Editorial Staff

References

- ↑

Belsky DW, Caspi A, Houts R, Cohen HJ, Corcoran DL, Danese A, et al. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(30):E4104-E10. doi: doi:10.1073/pnas.1506264112.

- ↑

López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194-217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. PubMed PMID: 23746838.

- ↑

- ↑

Alexis, Andrew F., et al. "Racial and ethnic differences in self-assessed facial aging in women: results from a multinational study." Dermatologic Surgery 45.12 (2019): 1635-1648.

- ↑

López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194-217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. PubMed PMID: 23746838.

Sreedhar A, Aguilera-Aguirre L, Singh KK. Mitochondria in skin health, aging, and disease. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(6):444. Epub 2020/06/11. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2649-z. PubMed PMID: 32518230; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7283348 Biosciences. A.S., L.A.-A., and K.K.S. hold equity in Yuva Biosciences.

- ↑

Sreedhar A, Aguilera-Aguirre L, Singh KK. Mitochondria in skin health, aging, and disease. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(6):444. Epub 2020/06/11. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2649-z. PubMed PMID: 32518230; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7283348 Biosciences. A.S., L.A.-A., and K.K.S. hold equity in Yuva Biosciences.

- ↑

Farage MA, Miller KW, Elsner P, Maibach HI. Characteristics of the Aging Skin. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013 Feb;2(1):5-10. doi: 10.1089/wound.2011.0356. PMID: 24527317; PMCID: PMC3840548.

- ↑

Jeong D, Qomaladewi NP, Lee J, Park SH, Cho JY. The Role of Autophagy in Skin Fibroblasts, Keratinocytes, Melanocytes, and Epidermal Stem Cells. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2020;140(9):1691-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2019.11.023

- ↑

Farage MA, Miller KW, Elsner P, Maibach HI. Characteristics of the Aging Skin. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013 Feb;2(1):5-10. doi: 10.1089/wound.2011.0356. PMID: 24527317; PMCID: PMC3840548.

- ↑

•

Skincare•

Inside Timeline’s Lab: Meet Mitochondria Expert Julie Faitg

•